1. Introduction

A. A Beginner at Golang

Hello! I am Kinon, an Indonesian Software Engineer from Money Forward. I have been working fullstack in this team for about 6 months. While I’ve gained solid experience in various programming languages and frameworks, I found myself wanting to dive deeper into Golang. To me Golang is a language that has been increasingly catching my attention due to its elegant approach to concurrency and system programming.

B. Motivation to Learn More Golang

Unfortunately, I did not get assigned to the last project that uses Golang in our organization. My exposure to Go has been limited to writing basic CRUD APIs during one of my university assignments, which only covered unary API patterns. This felt like just scratching the surface of what Golang could offer.

Even though I know Golang has tremendous potential across multiple domains:

- Microservices Architecture: Building scalable, distributed systems

- Concurrency and Parallelism: Leveraging goroutines and channels for efficient concurrent processing

- Stream Processing: Real-time data processing and reactive programming

- Machine Learning and Optimization: Performance-critical algorithms and computational tasks

- Systems Programming: Building robust, low-level applications

There’s a high probability of getting a chance to participate in future projects written in Golang within our organization. Rather than waiting for that opportunity, I decided to take initiative and build a personal project that would push me to explore Golang’s advanced features hands-on.

That’s why I embarked on building an “Adversarial Search Bot” – a project that would force me to learn and get comfortable with Golang’s unique features, particularly its concurrency model and advanced programming patterns!

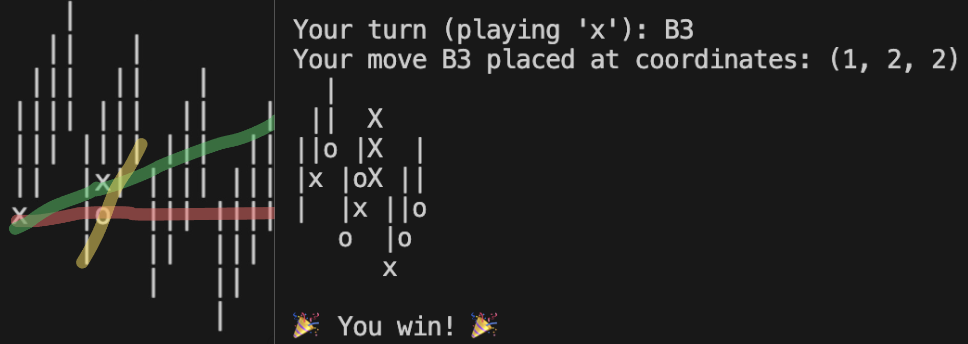

2. The Game We’re Tackling: 3D Tic-Tac-Toe

A. Why 3D Tic-Tac-Toe?

The choice of 3D Tic-Tac-Toe wasn’t random – it was inspired by several factors that aligned perfectly with my learning goals:

Inspiration from Chess Bots: I got inspired by a chess bot in our team’s Slack workspace (similar to the slackchess implementation in Go). I enjoy playing chess, so I wanted to implement a bot that I could match with my coworkers and have some fun during break times.

Personal Connection: I actually own a physical 3D Tic-Tac-Toe set! It’s incredibly fun when I play it with friends and family. Having a tangible reference helped me understand the game mechanics and win conditions more intuitively.

Scalability: The beauty of this choice is its flexibility – just by changing board dimensions, I can get regular 2D Tic-Tac-Toe, or even expand it to Connect 4 variants. The core algorithm remains the same while offering different complexity levels.

Advanced Golang Topics Coverage: Most importantly, implementing a sophisticated game AI surprisingly covers many advanced Golang concepts that I wanted to master:

- Goroutines: For concurrent game tree exploration

- Mutexes and Synchronization: Managing shared game state safely

- Context: Handling cancellation and timeouts in long-running searches

- Channels and Streams: Real-time communication between different AI components

B. How Does 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Work?

The game operates on a 4×4×4 cube, where any 4 pieces in a line in any direction constitutes a win. The winning conditions are more complex than traditional 2D Tic-Tac-Toe:

- 1-dimensional lines: Horizontal, vertical, or depth-wise (4 pieces in a straight line)

- 2D diagonal lines: Diagonals within any of the 2D planes (front, side, top faces)

- 3D diagonal lines: The four space diagonals that traverse the entire cube

Gravity Mechanics: Every column is affected by gravity – you cannot place a piece in an upper layer if the position below it is empty. This adds a strategic element similar to Connect 4, where players must consider the vertical stacking implications of their moves.

Here’s a glimpse of the core win-checking logic that handles all these complex winning patterns:

func (b *Board) checkWin() Player {

// Check all possible 4-in-a-row patterns

directions := [][3]int{

{1,0,0}, {0,1,0}, {0,0,1}, // 1D lines

{1,1,0}, {1,-1,0}, {1,0,1}, {1,0,-1}, {0,1,1}, {0,1,-1}, // 2D diagonals

{1,1,1}, {1,-1,-1}, {1,1,-1}, {1,-1,1}, // 3D diagonals

}

// Check all positions in all directions

for x := 0; x < b.Length; x++ {

for y := 0; y < b.Width; y++ {

for z := 0; z < b.Height; z++ {

for _, dir := range directions {

if winner := b.checkLine(x, y, z, dir[0], dir[1], dir[2]); winner != None { // checkline method is self-explanatory

return winner

}

}

}

}

}

return None

}The complexity of win detection in 3D space, combined with the gravity constraints, creates an excellent testbed for exploring sophisticated AI algorithms and concurrent programming patterns.

In the following sections, we’ll dive into the journey of building increasingly sophisticated bots – from basic minimax to concurrent streaming algorithms with persistent search trees – and discover how Golang’s concurrency features enabled some truly innovative approaches to game AI!

3. The Minimax Algorithm: Evaluation and Search Trees

A. Understanding Game Evaluation

Before diving into the search algorithm itself, we need a way to evaluate how good a board position is. The evaluation function is the brain that determines a board’s score – higher scores favor player one (‘x’) and lower scores favor player two (‘o’).

A good evaluation function should be:

- Symmetric: The score from player one’s perspective should be the negative of player two’s perspective

- Meaningful: It should reflect actual strategic advantage

- Efficient: Fast enough to be computed thousands of times during search

My Current Implementation Strategy:

For every possible winning line on the board (4 consecutive positions), I analyze the threat level:

- If a line contains only player one’s pieces (or empty cells), add score by

Baseto the power ofnumber_of_x_pieces - If a line contains only player two’s pieces (or empty cells), subtract score by

Baseto the power ofnumber_of_o_pieces - Mixed lines (containing both players’ pieces) contribute 0 to the score

func (b *Board) Evaluate() int {

score := 0

// ... check all positions and directions

for idx := 0; idx < b.Volume; idx++ {

i, j, k := b.idxToCoord(idx) // self explanatory

for _, dir := range directions {

// ... get line and count pieces

line := b.GetLine([3]int{i, j, k}, dir)

xCount := countBytes(line, 'x')

oCount := countBytes(line, 'o')

// Exponential scoring for threats

if xCount > 0 && oCount == 0 {

score += int(math.Pow(float64(b.Base), float64(xCount)))

} else if oCount > 0 && xCount == 0 {

score -= int(math.Pow(float64(b.Base), float64(oCount)))

}

}

}

return score

}With this approach, to achieve a higher score, each player is incentivized to simultaneously:

- Create threats: Occupy cells that generate more potential winning lines

- Block opponent threats: Prevent player two from forming their own winning lines

The exponential scoring (Base to the power of pieces) means that having 3 pieces in a line is much more valuable than having 3 separate lines with 1 piece each – this encourages focused, aggressive play.

Complexity: O(N⁴) where N is the board dimension, as we check every position in every direction.

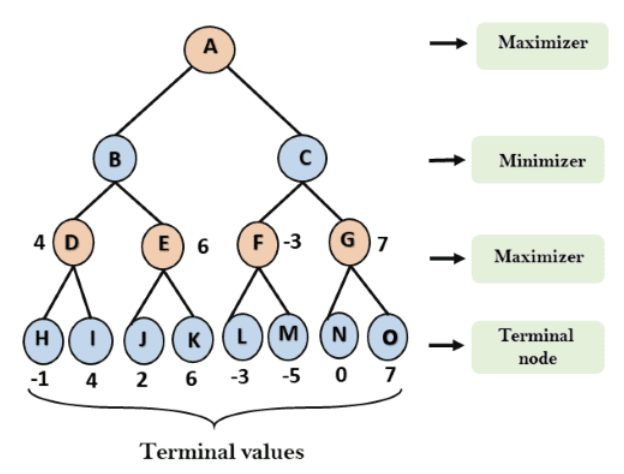

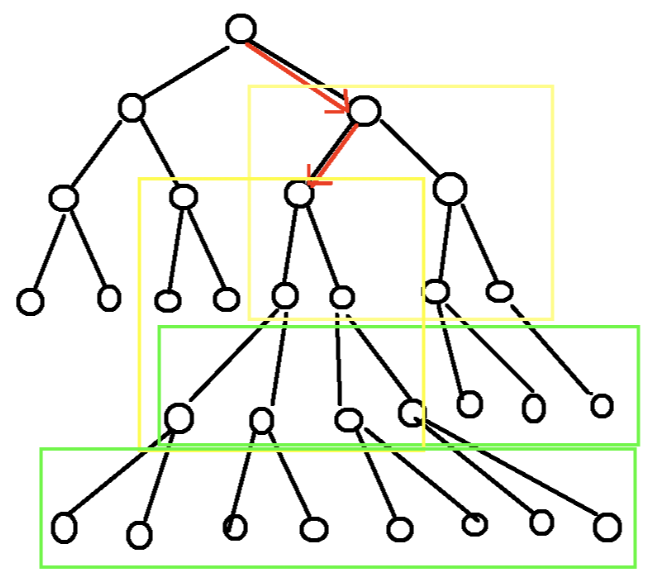

B. The Minimax Search Tree

Searching through every possible future game state for a certain number of moves ahead forms a tree structure. Each level represents alternating players – one trying to maximize the evaluation score, the other trying to minimize it.

Based on the values propagated up from the tree’s leaves back to the root, our bot can decide which move leads to the best possible outcome (assuming both players play optimally).

The minimax algorithm works by:

- Leaf nodes: Evaluate board positions at maximum search depth

- Minimizing nodes: Choose the minimum score among children (opponent’s turn)

- Maximizing nodes: Choose the maximum score among children (our turn)

- Propagation: Values bubble up through the tree to determine the best root move

4. Introducing Concurrency to Minimax

This is where my Golang learning journey got truly exciting! The minimax algorithm is embarrassingly parallel – each branch of the search tree can be explored independently. This was my first real encounter with Go’s concurrency primitives.

A. Learning Go’s Sync Package

I discovered three fundamental tools that would become essential throughout this project:

- sync.WaitGroup: Coordinate multiple goroutines to finish before proceeding

- Goroutines: Lightweight threads that make concurrent execution possible

- Channels: Communication pipes between goroutines, allowing data to flow safely

B. My First Concurrent Implementation

Here’s the core of my ConcurrentMinimaxDeep function that implements concurrency at every level of the minimax tree:

func concurrentMinimaxDeep(board *Board, depth int, isMaximizing bool) (int, []string) {

// ... handle base cases (terminal conditions, depth limit)

validMoves := board.GetValidMoves()

// ... handle edge cases and small branches

// Channel to collect results from goroutines

type DepthResult struct {

Move string

Score int

Moves []string

}

results := make(chan DepthResult, len(validMoves))

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Launch a goroutine for each possible move

for _, move := range validMoves {

wg.Add(1)

go func(move string) {

defer wg.Done()

// Create a deep copy of the board to test the move

testBoard := copyBoard(board)

testBoard.Move(move, symbol)

// Recursively evaluate this branch with deep concurrency

score, moves := concurrentMinimaxDeep(testBoard, depth-1, !isMaximizing)

results <- DepthResult{Move: move, Score: score, Moves: moves}

}(move)

}

// Close results channel when all goroutines are done

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

// ... collect and find best result from all branches

for result := range results {

if isMaximizing && result.Score > bestScore {

bestScore = result.Score

bestMoves = append([]string{result.Move}, result.Moves...)

}

// ... handle minimizing case

}

return bestScore, bestMoves

}C. Key Learning Moments

WaitGroup Discovery: sync.WaitGroup became my go-to tool for ensuring all goroutines complete before collecting results. The pattern of wg.Add(1) before launching a goroutine and defer wg.Done() inside it became second nature.

Channel Communication: Using a buffered channel make(chan DepthResult, len(validMoves)) allowed goroutines to send their results without blocking. The custom DepthResult struct enabled me to send complex data through the channel cleanly.

Goroutine Lifecycle: I learned the importance of proper goroutine cleanup by using an additional goroutine to close the results channel after all workers finish – preventing deadlocks when ranging over the channel.

This concurrent approach dramatically improved performance on multi-core systems, turning the minimax algorithm from a sequential bottleneck into a parallel powerhouse that could explore much deeper game trees in the same amount of time!

5. Performance Optimizations: From Theory to Practice

As I dove deeper into game AI development, I discovered that raw concurrency was just the beginning. Two critical optimizations emerged that would dramatically reshape the performance characteristics of my bots.

A. Delta Evaluation & Depth First Search

The Problem: My evaluation function was running in O(N⁴) complexity – recalculating the entire board score for every single move in the search tree.

The Insight: When placing a single piece, I don’t need to re-evaluate the entire board. The change in score can be observed by analyzing only the lines that pass through the newly placed piece.

// DeltaEvaluate: Only check lines affected by the new piece

func (b *Board) DeltaEvaluate(x, y, z int, updateWin bool) int {

// ... get piece symbol and initialize delta

// For each direction, check all lines that pass through this position

for _, dir := range directions {

for offset := -(b.WinLength - 1); offset <= 0; offset++ {

// ... calculate line bounds

// Get the current line (with the piece already placed)

lineAfter := b.GetLine([3]int{startX, startY, startZ}, dir)

xCountAfter := countBytes(lineAfter, 'x')

oCountAfter := countBytes(lineAfter, 'o')

// Calculate score contribution with the piece

scoreAfter := 0

if xCountAfter > 0 && oCountAfter == 0 {

scoreAfter += int(math.Pow(float64(b.Base), float64(xCountAfter)))

}

// ... calculate scoreBefore and add delta

}

}

return delta

}Performance Gain: Reduced evaluation complexity from O(N⁴) to O(N²) – a 16x improvement on our 4x4x4 board!

Implementing UnMove for DFS

To maximize this optimization, I needed to avoid copying boards entirely. Enter the UnMove function:

func (b *Board) UnMove(moveStr string) [3]int {

// ... parse move and find piece position

// Calculate the delta before removing the piece

delta := b.DeltaEvaluate(col, row, topHeight, false)

b.Grid[col][row][topHeight] = '|'

b.CurrentHeights[col][row]--

b.Score -= delta

return [3]int{col, row, topHeight}

}The Trade-off: This optimization is perfectly compatible with depth-first search but not fully compatible with concurrent implementations. Why? Because goroutines need independent board copies to avoid race conditions. Delta evaluation still helps (reducing to O(N³)), but we lose the full benefit of avoiding board copies.

B. Improvement 2: Check Detection & Forcing Moves

The Chess Inspiration: In chess, when you’re in “check” you must respond to the immediate threat. This same concept applies brilliantly to 3D Tic-Tac-Toe!

The Implementation: I can detect “check” situations with the same O(N²) complexity as delta evaluation – by analyzing lines connected to the last placed piece.

// Check threat detection (from board.go Print method)

if emptyCount == 1 && (oCount == 0 || xCount == 0) {

// Find the critical empty cell

for pos := 0; pos < b.WinLength; pos++ {

if b.Grid[x][y][z] == '|' {

criticalCell = [3]int{x, y, z}

break

}

}

// Check if the critical cell can actually be played (gravity rules)

canBePlayed := (criticalCell[2] == b.CurrentHeights[criticalCell[0]][criticalCell[1]])

if canBePlayed {

// This is a forcing move - opponent MUST respond here

// Highlight threat with capital letters and '#' for critical cell

}

}The Strategic Impact: When a player creates a “check” (3 pieces in a line with 1 playable empty space), the opponent can only respond to at most one position. This dramatically:

- Reduces branching factor: From up to 16 possible moves to just 1 critical response

- Enables deeper search: With fewer branches to explore, we can search much deeper

- Works universally: Benefits both sequential and concurrent implementations equally

Forcing Move Strategy: This creates a powerful strategic pattern:

- Offensive: Create multiple simultaneous threats (forcing the opponent into impossible choices)

- Defensive: Always respond to immediate threats before pursuing your own strategy

- Search Enhancement: The minimax tree becomes much more focused and efficient

These optimizations transformed my bot from a brute-force calculator into a strategic player that could think several moves ahead while running efficiently on both single-threaded and multi-core systems!

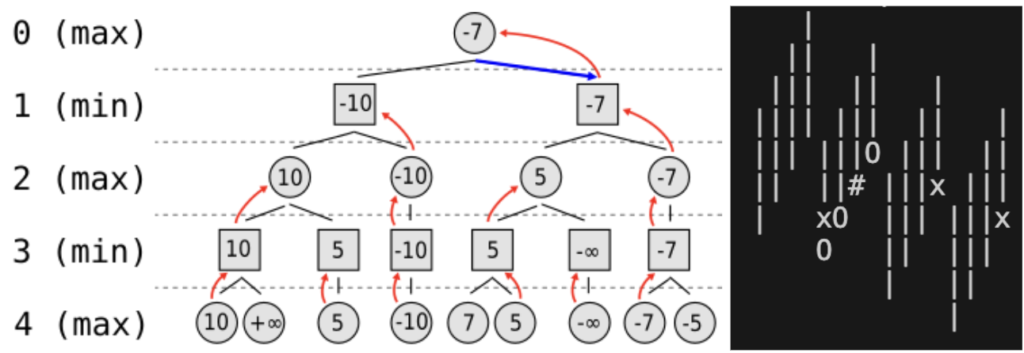

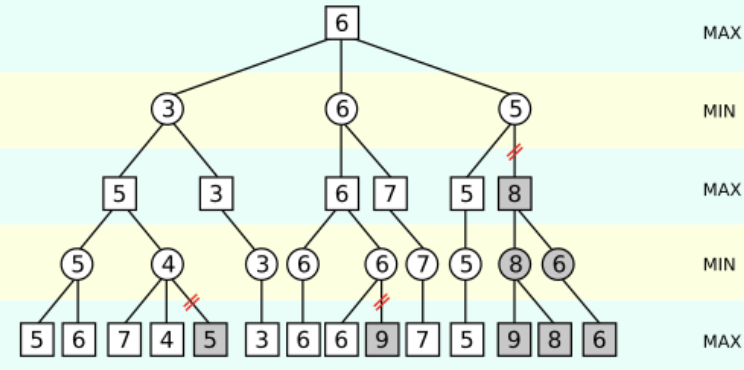

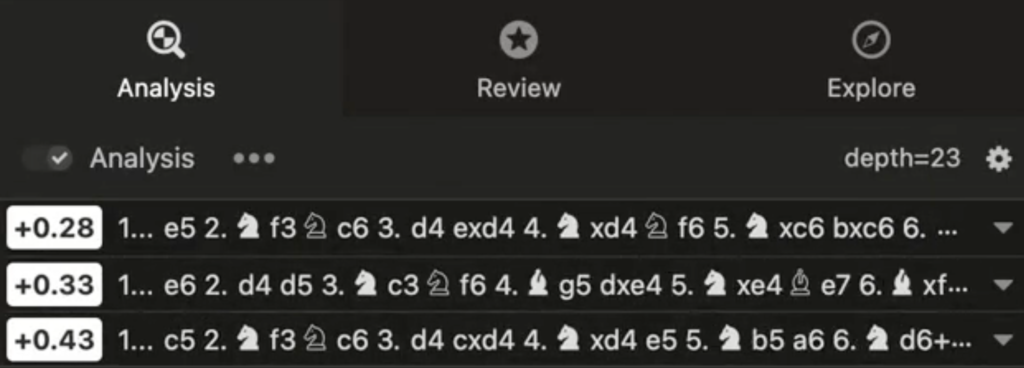

C. Improvement 3: Alpha-Beta Pruning

The Core Insight: Because minimax alternates between maximizing and minimizing layers, we can eliminate entire subtrees from search when we know they won’t influence the final result.

How It Works: The algorithm maintains bounds (alpha and beta) representing the best guaranteed scores for the maximizing and minimizing players respectively. When a branch’s score exceeds these bounds, we can safely “prune” it – skipping the evaluation of its remaining children.

Example from the Diagram: Consider the leftmost pruning scenario:

- The 3rd layer (maximizing) already found a score of 5 from its first child

- When evaluating the second child (minimizing layer), it finds a score of 4

- Since the minimizing layer will return ≤4, and the maximizing layer already has 5, this entire subtree can be pruned – no need to explore further!

func alphaBetaMinimax(board *Board, depth int, isMaximizing bool, threshold int) (int, []string) {

// ... handle base cases (terminal conditions, depth limit)

// Initialize best score based on player type

var symbol byte = 'x'

currentScore := MIN_INT

if !isMaximizing {

symbol = 'o'

currentScore = MAX_INT

}

for _, move := range board.GetValidMoves() {

board.Move(move, symbol)

// Recursively search with current best as threshold

score, moves := alphaBetaMinimax(board, depth-1, !isMaximizing, currentScore)

board.UnMove(move)

if isMaximizing {

if score > currentScore {

currentScore = score

bestMoves = append([]string{move}, moves...)

}

// Pruning condition: if our score >= threshold, parent won't choose this

if currentScore >= threshold {

break // Parent is minimizing and won't select this branch

}

} else {

if score < currentScore {

currentScore = score

bestMoves = append([]string{move}, moves...)

}

// Pruning condition: if our score <= threshold, parent won't choose this

if currentScore <= threshold {

break // Parent is maximizing and won't select this branch

}

}

}

return currentScore, bestMoves

}Perfect DFS Compatibility: Alpha-beta pruning is ideally suited for depth-first search implementations. The sequential nature of DFS allows the algorithm to:

- Build bounds progressively: Each evaluated branch updates the alpha/beta bounds

- Prune effectively: Later branches can be skipped based on earlier discoveries

- Maintain state: The move/unmove pattern preserves board state perfectly

- Order matters: Good move ordering (evaluating promising moves first) dramatically increases pruning effectiveness

Performance Impact: In the best case, alpha-beta pruning can reduce the search tree from O(b^d) to O(b^(d/2)), where b is the branching factor and d is the depth. For my 3D Tic-Tac-Toe bot, this meant I am able to increase search depth from 5 to 7 while maintaining the same response time.

The Sequential Advantage: Unlike my concurrent implementations that needed careful synchronization, alpha-beta pruning thrived on the deterministic, ordered exploration that DFS provided. This became a crucial lesson: sometimes the most elegant algorithmic improvement comes from working with your execution model rather than against it.

6. Concurrent Alpha-Beta: The Ultimate Challenge

While alpha-beta pruning works beautifully in sequential code, implementing it concurrently opened up an entirely new dimension of Go programming concepts. This pushed me to learn some of the most sophisticated concurrency patterns in the language.

A. The Concurrent Pruning Problem

In sequential alpha-beta, pruning is straightforward – we evaluate moves one by one and can immediately stop when a threshold is exceeded. But in concurrent execution:

- Multiple goroutines evaluate different moves simultaneously

- Shared threshold needs to be updated as better moves are discovered

- Early termination must coordinate across all active goroutines

This required mastering three advanced Go concurrency concepts I hadn’t encountered before.

B. Learning Go’s Context Package

Context for Cancellation: The context package became my tool for coordinating early termination across goroutine hierarchies.

func concurrentAlphaBetaMinimaxStream(board *Board, depth int, isMaximizing bool, parentCtx context.Context) <-chan StreamResult {

// ... setup

// Create cancellable context for child goroutines

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(parentCtx)

defer cancel()

// Launch goroutines for each move

for _, move := range validMoves {

wg.Add(1)

go func(move string) {

defer wg.Done()

// ... board setup

// Pass context to children for pruning coordination

childCh := concurrentAlphaBetaMinimaxStream(testBoard, depth-1, !isMaximizing, ctx)

for childResult := range childCh {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Pruned by parent - stop immediately!

case childResults <- StreamResult{Move: move, Score: childResult.Score, Final: childResult.Final}:

}

}

}(move)

}

// When we find a pruning condition, cancel all children

if (isMaximizing && bestScore >= MAX_INT/3) {

cancel() // Signal children to stop

break

}

}C. Shared Memory with Mutex Protection

Thread-Safe Score Updates: The current best score becomes shared state that multiple goroutines need to read and update safely. This was my introduction to sync.Mutex.

type PruningState struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

bestScore int

bestMove string

canPrune bool

}

func (ps *PruningState) UpdateScore(score int, move string, isMaximizing bool) bool {

ps.mu.Lock()

defer ps.mu.Unlock()

improved := false

if (isMaximizing && score > ps.bestScore) || (isMaximizing && score < ps.bestScore) {

ps.bestScore = score

ps.bestMove = move

improved = true

}

// Check pruning condition

ps.canPrune = (isMaximizing && ps.bestScore >= threshold) ||

(!isMaximizing && ps.bestScore <= threshold)

return improved

}D. Streaming Results with Channel Fan-In

Real-Time Updates: Instead of waiting for all moves to complete, I wanted to stream better moves as soon as they were discovered. This required a fan-in pattern to collect streams from all child goroutines.

// Channel to collect all streams from children (fan-in pattern)

childResults := make(chan StreamResult, len(validMoves)*2)

// Each child goroutine streams its results

for _, move := range validMoves {

go func(move string) {

// ... setup and recursive call

// Forward all streaming results from child

for childResult := range childCh {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Parent cancelled - stop forwarding

case childResults <- StreamResult{

Move: move,

Score: childResult.Score,

Final: childResult.Final,

}:

}

}

}(move)

}

// Process streaming results as they arrive

for result := range childResults {

// Update shared state thread-safely

if improved := pruningState.UpdateScore(result.Score, result.Move, isMaximizing) {

// Stream improvement to parent immediately

resultCh <- StreamResult{Move: result.Move, Score: result.Score, Final: false}

// Check if we can now prune remaining children

if pruningState.CanPrune() {

cancel() // Stop all remaining goroutines

break

}

}

}E. The Complexity Trade-off

This concurrent alpha-beta implementation was significantly more complex than the sequential version, but it provided unique benefits:

Advantages:

- Real-time streaming: Better moves surface immediately, not at the end

- Parallel exploration: Multiple branches explored simultaneously

- Responsive UI: Can show “thinking” progress in real-time

- Scalable performance: Leverages all CPU cores effectively

Challenges:

- Reduced pruning efficiency: Concurrent evaluation means less optimal move ordering

- Synchronization overhead: Mutex locks and channel operations add cost

- Complex debugging: Race conditions and deadlocks became real concerns

Learning Outcome: This exercise taught me that concurrency isn’t always about raw performance – sometimes it’s about creating more responsive, interactive systems. The streaming alpha-beta became the foundation for real-time game analysis features that simply weren’t possible with sequential algorithms.

7. PvE Stream Mode: Server-Side Streaming in Action

Building on the concurrent alpha-beta foundation, I wanted to create something that felt like a modern web application – real-time analysis that gets progressively better as the system thinks deeper. This led me to implement what’s essentially server-side streaming for game AI.

A. The Server-Side Streaming Concept

In traditional request-response models, you make a request and wait for the complete result. But in streaming systems:

- Client initiates request: “What’s the best move?”

- Server starts processing: Multiple concurrent analysis streams begin

- Progressive results: Better moves stream back as they’re discovered

- Client updates in real-time: Shows improving analysis without waiting for completion

B. Multi-Depth Concurrent Analysis

Instead of running a single bot at fixed depth, I created a competitive multi-depth system where different depth bots race to find the best moves:

func RunPvEStream() {

// Define multiple analysis depths running concurrently

depths := []int{3, 4, 5, 6, 7}

fmt.Println("🤖 Multi-Depth Bot is analyzing...")

// Start streaming analysis across all depths

resultCh := multiDepthAlphaBetaStream(board, false, depths)

// Listen to progressive improvements

for result := range resultCh {

if result.Final {

finalResult = result

break

}

// Show real-time updates as better moves are found

movesStr := strings.Join(result.Moves, " → ")

fmt.Printf("📈 New best move from depth %d: [%s] (Score: %d)\n",

result.Depth, movesStr, result.Score)

}

// Execute the final best move

fmt.Printf("🎯 Final decision from depth %d: [%s]\n",

finalResult.Depth, finalResult.Moves)

}C. How the Streaming Works

The magic happens through goroutine result propagation:

- Multiple depth bots start analyzing simultaneously (depths 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

- Shallow bots finish first, streaming their initial best moves

- Deeper bots eventually find better moves, streaming improvements

- Parent goroutine collects all streams and forwards the best results

- Client sees progress: “Depth 3 suggests A1… Depth 5 found better move B2… Depth 7 confirms C3!”

// Each depth runs its own streaming analysis

for _, depth := range depths {

go func(depth int) {

// Get streaming results from this specific depth

streamCh := concurrentAlphaBetaMinimaxStreamWithSequence(board, depth, isMaximizing, ctx)

// Forward results with depth information

for result := range streamCh {

depthResults <- MultiDepthStreamResult{

Moves: result.Moves,

Score: result.Score,

Depth: depth, // Tag with depth for prioritization

Final: result.Final,

}

}

}(depth)

}

// Process streaming results with depth-aware prioritization

for result := range depthResults {

// Deeper analysis gets priority even with same score

improved := false

if result.Depth > bestDepth ||

(result.Score > bestScore && result.Depth == bestDepth) {

bestScore = result.Score

bestMoves = result.Moves

bestDepth = result.Depth

improved = true

}

// Stream improvement immediately to client

if improved {

resultCh <- MultiDepthStreamResult{

Moves: bestMoves,

Score: bestScore,

Depth: bestDepth,

Final: false, // More improvements might be coming

}

}

}D. The User Experience

This creates an engaging analysis experience that feels like watching a chess engine think:

🤖 Multi-Depth Bot is analyzing...

─────────────────────────────────────

📈 New best move from depth 3: [B2] (Score: -45)

📈 New best move from depth 4: [A1 → C3] (Score: -23)

📈 New best move from depth 5: [B2 → A1 → D4] (Score: -12)

📈 New best move from depth 6: [C1 → B2 → A3] (Score: -8)

─────────────────────────────────────

🎯 Final decision from depth 6: [C1 → B2 → A3]

🤖 Bot plays C1 at (2, 0, 0) - Time: 1.2sE. Learning Server-Side Streaming Patterns

This implementation taught me several key streaming concepts:

Progressive Enhancement: Start with quick, approximate results and improve over time Competitive Processing: Multiple workers racing to provide better solutions Priority-Based Merging: Deeper analysis takes precedence over shallow results Real-Time Feedback: Users see the system “thinking” and improving its analysis Graceful Termination: Can stop early if time constraints require it

The streaming approach transformed the bot from a “black box that eventually gives an answer” into a transparent thinking process that users could follow in real-time. This pattern could easily be adapted for web APIs, real-time dashboards, or any system where progressive results are more valuable than waiting for perfect answers!

8. The Ultimate Challenge: Bidirectional Streaming in EvE Mode

The final frontier of my Golang learning journey was implementing bidirectional streaming – where both bots could simultaneously utilize their opponent’s thinking time to calculate ahead. This was the most sophisticated concurrency challenge I had ever tackled.

A. The Core Innovation: Persistent Search Trees

Main Idea: Instead of recalculating from scratch each turn, both bots maintain persistent search trees that continue growing during opponent thinking time.

The breakthrough insight was realizing that game AI could work like a background service:

- Game start: Bot searches deeply (multiple layers)

- Each turn: Bot only needs to search one additional layer

- Tree maintenance: After opponent’s move, shift root node and prune irrelevant branches

- Continuous calculation: Keep expanding the tree regardless of whose turn it is

type PersistentMinimaxBot struct {

Symbol byte

Name string

InitialDepth int

// Persistent tree that grows continuously

rootNode *SearchNode

tree *SearchTree

mutex sync.RWMutex // Protect concurrent access to tree

}

// Background calculation continues during opponent's turn

func (bot *PersistentMinimaxBot) MakeMove(board *Board) (string, [3]int) {

// Tree has been calculating in background - just extract best move!

bot.mutex.RLock()

bestMove := bot.rootNode.bestChild.Move

bot.mutex.RUnlock()

// Execute move and shift tree root

coords := board.Move(bestMove, bot.Symbol)

bot.moveRoot(bestMove) // Shift root, prune old branches

return bestMove, coords

}B. The Bidirectional Streaming Magic

When both bots use this approach, you get true bidirectional streaming:

- Bot A thinks: Bot B utilizes this time to expand its search tree

- Bot A moves: Bot B instantly responds (pre-calculated) and starts thinking

- Bot B thinks: Bot A now utilizes this time to expand its search tree

- Continuous cycle: Both bots are always calculating, never idle

func RunEvEStream() {

// Two persistent bots with background calculation

botX := NewPersistentMinimaxBot('x', "PersistentBot-X", 4, 10)

botO := NewPersistentMinimaxBot('o', "PersistentBot-O", 4, 10)

for {

// Active bot makes move (waiting bot continues calculating)

move, coords = activeBot.MakeMove(board)

// Notify waiting bot about opponent's move for tree pruning

waitingBot.OpponentMove(move)

// Both bots now have fresh information to continue calculating

// The cycle continues...

}

}C. Advanced Golang Concurrency Patterns Learned

This implementation pushed me to master the most sophisticated concurrency concepts:

RWMutex for Concurrent Tree Access: Multiple goroutines reading the tree while background threads update it safely.

// Multiple readers can access tree simultaneously

func (tree *SearchTree) getBestMove() string {

tree.mutex.RLock()

defer tree.mutex.RUnlock()

return tree.rootNode.bestChild.Move

}

// Writers get exclusive access for tree modifications

func (tree *SearchTree) expandNode(nodeID string) {

tree.mutex.Lock()

defer tree.mutex.Unlock()

// Safely modify tree structure

}Goroutine Termination Management: Coordinating the lifecycle of background calculation threads.

// Graceful shutdown of background goroutines

func (bot *PersistentMinimaxBot) Close() {

bot.tree.cancel() // Cancel all background operations

bot.tree.wg.Wait() // Wait for all goroutines to finish

// Clean shutdown guaranteed

}Pipeline Processing: Streaming tree expansions through processing pipelines.

// Pipeline: Tree expansion -> Score propagation -> Move evaluation

expandCh := make(chan *SearchNode, 100)

scoreCh := make(chan *SearchNode, 100)

bestMoveCh := make(chan string, 10)

// Multi-stage pipeline processing

go expandNodes(expandCh, scoreCh) // Stage 1: Expand tree nodes

go propagateScores(scoreCh, bestMoveCh) // Stage 2: Update minimax scores

go updateBestMoves(bestMoveCh) // Stage 3: Update best move cacheD. The Performance Revolution

The results were game-changing (literally):

- Response time: From 1-2 seconds to microseconds (pre-calculated moves)

- Search depth: Continuously growing deeper throughout the game

- Strategic play: Bots demonstrated long-term planning and positional understanding

- Resource utilization: 100% CPU usage – no idle time between turns

E. Real-World Applications

This bidirectional streaming pattern has broad applicability:

- Real-time systems: Continuous background processing with instant responses

- Microservices: Services that pre-calculate responses during request processing

- Game engines: Background AI that adapts to player actions

- Financial systems: Continuous risk calculation with instant trade execution

- ML pipelines: Models that retrain continuously while serving predictions

Learning Outcome: This project taught me that the most powerful concurrent systems aren’t just about doing things faster – they’re about never stopping. By eliminating idle time and creating truly reactive systems, Go’s concurrency primitives facilitate architectures that are often cumbersome to implement in other languages.

9. What’s Next for This Project?

As I reflect on this journey, there are several exciting directions this project could evolve:

Bit-Level Board Optimization: Since each board cell has only 3 states (empty, X, O), I can represent each position in just 2 bits. This means the entire 4×4×4 board (64 cells) could fit in just 16 bytes instead of a 3D array of symbols. This bit-packed representation could dramatically speed up board operations and memory usage.

Advanced Evaluation Functions: Experiment with different evaluation strategies or hybrid approaches that combine multiple evaluation methods. Maybe weighted combinations of positional, tactical, and strategic factors.

Slack Bot Deployment: Deploy this as a Slack bot so I can use it in my team’s Slack and challenge my coworkers! The competitive element would make it much more engaging.

Chess.com-Style Platform: Build a simple website where people can match against each other, complete with ELO ratings and post-game analysis features. The streaming analysis could provide real-time move commentary.

Puzzle Generation: Extract forcing move sequences from actual games to create tactical puzzles. Every time the bot detects a forcing sequence during play, I could save it as a training puzzle for other players.

10. Lessons Learned

A. Before Starting the Project

My preparation involved several key learning activities:

- Reading “Concurrency in Go”: This book provided the theoretical foundation for understanding Go’s concurrency model

- Refreshing Go syntax with LeetCode: Solved various problems to get comfortable with Go’s syntax and idioms

- Exploring existing codebases: Studied repositories like the team’s audit logging system to understand real-world Go patterns

- Following learning roadmaps: Used resources like roadmap.sh/golang to structure my learning path

B. After Working on the Project

The hands-on experience taught me lessons that no book or tutorial could:

There is no such thing as a perfect plan. Sometimes I need to just start implementing “just enough” functionality first, then refactor and improve iteratively. The progression from naive minimax → concurrent → streaming → persistent search happened organically through these improvements.

Go makes concurrency/parallelism remarkably accessible compared to my previous experience with C++ or Python. The language design genuinely simplifies what are typically complex concurrent programming patterns.

Concurrent programming becomes very beneficial when you don’t reinvent the wheel. Throughout this project, I learned progressively sophisticated patterns:

- WaitGroup and goroutine management when implementing Concurrent Minimax

- Mutex, confinement, and Context when implementing Concurrent Alpha-Beta Pruning

- Server streaming, fan-out and fan-in patterns when implementing Bot Game Analysis

- Bidirectional streaming and Pipeline processing when implementing the most challenging feature: persistent search trees with background calculation

Each concept built naturally on the previous one, creating a learning progression that felt both challenging and achievable. Go’s concurrency primitives didn’t just make these patterns possible – they made them elegant and maintainable.

Happy Coding 🚀