Hello! My name is Hamonangan, a full-stack software engineer at Money Forward Cloud HRIS, and a fan of Go programming language (Golang). As Money Forward Engineers, we actively use Go in our codebase and proudly sponsor related events such as 2025 Go Conference.

A Brief about Go

Go is a statically typed, compiled programming language that has a good reputation for network and concurrent programming. On top of that, it also has robust package management, lightweight build executables, and a set of tools to enforce consistent code formatting, like go fmt and go mod. Go is also a popular language recently. In 2024, there are approximately 4.1 million developers using Go.

Despite its popularity, Go standard library has limited advanced data structures and algorithms (compared to Java or C++ STL, for instance). Although it can be challenging to implement, Go has unique features that make some implementations of data structures and algorithms actually interesting. In this article, we will explore some of them!

1. Set using Empty Struct

Set is a data structure that collects unique elements. For example, C++ has std::set<int> s to declare a set of integers. However, at the time of writing, Go standard library doesn’t have a set implementation.

To achieve a set data structure in such a programming language, map data structure, which has unique keys can be used. In Go’s case, we can create var s = map<string>bool to create a set of unique strings. Interestingly, we can also use an empty struct as a value, as shown here.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

s := make(map[string]struct{})

s["alice"] = struct{}{}

s["bob"] = struct{}{}

if _, ok := s["bob"]; ok {

fmt.Println("Bob exist!")

}

delete(s, "bob")

if _, ok := s["bob"]; !ok {

fmt.Println("Bob no longer exist...")

}

}Compared to using boolean values that take bytes of memory, the key advantage of this approach is that the empty struct{} takes zero memory. In every case, unsafe.Sizeof(struct{}{}) always returns 0. Therefore, the memory space is allocated only for the map keys. Dave Cheney makes a detailed explanation of empty struct space allocation. The article also mentions practical uses of empty structs, such as method receivers and signals.

With that being said, there is no reason not to implement a set from a map, which is what Go already has!

2. Queue using Buffered Channel

Queue is a data structure that allows two operations: insertion of an element and deletion of the first element added. Hence, the term FIFO (First In First Out). There are several ways to implement a queue, either by an array (slice) or a linked list (as implemented by container/list standard library).

type Queue []any

func (q *Queue) Enqueue(v any) {

(*q) = append((*q), v)

}

func (q *Queue) Dequeue() any {

ret := (*q)[0]

(*q) = (*q)[1:]

return ret

}However, we can also construct a queue using buffered channel. The syntax is also very interesting.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

q := make(chan string, 100)

q <- "Alice"

q <- "Bob"

fmt.Println(<-q) // Alice

q <- "Charlie"

fmt.Println(<-q) // Bob

}Here we can see that the syntax is intuitive if we think of Go channel as a queue, with “arrow keys” indicating in and out operations.

Despite its elegance, implementing a queue using a buffered channel is considered impractical. Quoting The Go Programming Language book, “Novices are sometimes tempted to use buffered channels within a single goroutine as a queue, lured by their pleasingly simple syntax, but this is a mistake… If all you need is a simple queue, make one using a slice”.

There are several reasons for this impracticality. First, most programming languages support peek operation (reading the first element without removing it). It is impossible to do with channels. Buffered channels also have limited capacity and cause a deadlock at full capacity.

Although not idiomatic, this approach is an interesting way to explore Go channel features.

3. Priority Queue with Heap

Unlike Java or C++ standard library, which have PriorityQueue, Go doesn’t have a straightforward priority queue implementation. Priority queue resembles a queue, but instead of deleting the first element, it deletes the element with the highest priority. The most efficient way to implement it is with a max heap.

Fortunately, Go has container/heap package that we can use to implement a heap. It has heap.Interface which needs to be implemented by our priority queue. Interestingly, heap works as a min heap, so we need to tweak our type to work as a max heap. This is demonstrated neatly by container/heap documentation.

// An Item is something we manage in a priority queue.

type Item struct {

value string // The value of the item; arbitrary.

priority int // The priority of the item in the queue.

// The index is needed by update and is maintained by the heap.Interface methods.

index int // The index of the item in the heap.

}

// A PriorityQueue implements heap.Interface and holds Items.

type PriorityQueue []*Item

func (pq PriorityQueue) Len() int { return len(pq) }

func (pq PriorityQueue) Less(i, j int) bool {

// We want Pop to give us the highest, not lowest, priority so we use greater than here.

return pq[i].priority > pq[j].priority

}

func (pq PriorityQueue) Swap(i, j int) {

pq[i], pq[j] = pq[j], pq[i]

pq[i].index = i

pq[j].index = j

}

func (pq *PriorityQueue) Push(x any) {

n := len(*pq)

item := x.(*Item)

item.index = n

*pq = append(*pq, item)

}

func (pq *PriorityQueue) Pop() any {

old := *pq

n := len(old)

item := old[n-1]

old[n-1] = nil // don't stop the GC from reclaiming the item eventually

item.index = -1 // for safety

*pq = old[0 : n-1]

return item

}Let’s take a look at Less method. The Go container/heap implementation sorts items in ascending order (from the lowest at the top to the highest at the bottom). However, because we want the highest priority values to be at the top of the heap, so contrary to what the name suggests, the Less comparison checks whether the value is greater.

Now, let’s test our PriorityQueue type with some data as following.

func main() {

pq := make(PriorityQueue, 2)

pq[0] = &Item{value: "Bob", priority: 2, index: 0}

pq[1] = &Item{value: "Charlie", priority: 1, index: 1}

heap.Init(&pq)

heap.Push(&pq, &Item{value: "Alice", priority: 3, index: 2})

for pq.Len() > 0 {

item := heap.Pop(&pq).(*Item)

fmt.Printf("%.2d:%s ", item.priority, item.value) // "03:Alice 02:Bob 01:Charlie"

}

}The queue Pop method returns Alice, Bob, and then Charlie respectively.

Although we need to manually construct the type and its nodes, we don’t need to implement the heap by ourselves (which is difficult to optimize by hand as sort.Sort is). Therefore, this is a practical way to implement a priority queue in Go.

4. Equivalent Binary Search Tree Check with Goroutine

This is another interesting Go use case taken from the famous Go Tour exercise. The problem is checking whether two binary search trees are equivalent using concurrency and channels. A binary search tree is a data structure that holds unique and sorted data in the form of a binary tree. Hence, we can perform a binary search operation on it.

Spoiler alert! If you want to solve the exercise by yourself, stop here. Continue reading after trying to do it on the platform.

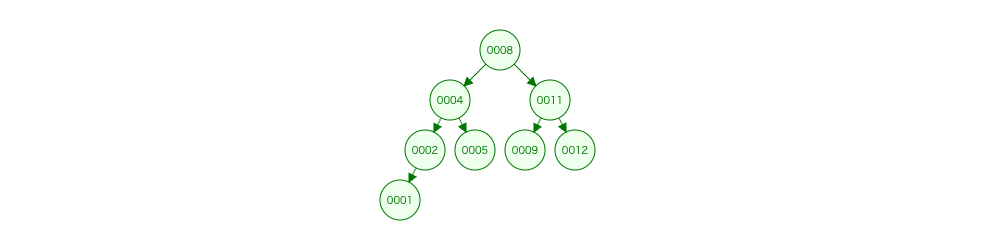

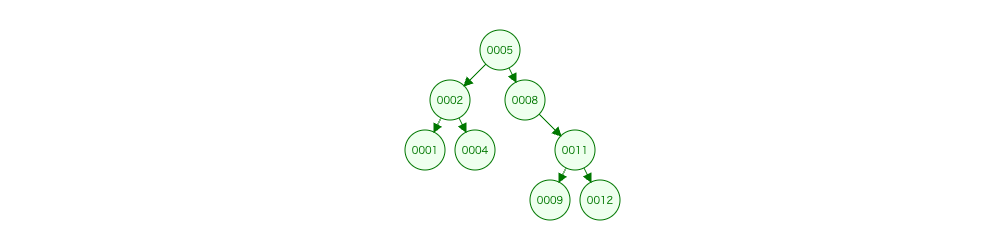

For example, these two binary search trees are considered equivalent. Although they have different structures, they have exactly the same elements.

We will solve this problem using two functions: walk and same. Walk function is basically inorder traversal algorithm. However, we can pass traversed nodes to a channel instead of storing all the node values in an array.

func Walk(t *tree.Tree, ch chan int) {

if t != nil {

Walk(t.Left, ch)

ch <- t.Value

Walk(t.Right, ch)

}

}Next, we can use walk concurrently in our same function. Here, we call 2 goroutines with go Walk and repeatedly receive results from 2 different channels. Given that the values are guaranteed in a sorted order, we can compare the sameness of both values.

func Same(t1, t2 *tree.Tree) bool {

ch1 := make(chan int)

ch2 := make(chan int)

go Walk(t1, ch1)

go Walk(t2, ch2)

for range 10 {

curT1 := <-ch1

curT2 := <-ch2

if curT1 != curT2 {

return false

}

}

return true

}Finally, we can test our solution in our main function. Since tree.Tree API returns a random tree, feel free to run the test multiple times to check the consistency of our solution.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"golang.org/x/tour/tree"

)

// Walk walks the tree t sending all values

// from the tree to the channel ch.

func Walk(t *tree.Tree, ch chan int) {

if t != nil {

Walk(t.Left, ch)

ch <- t.Value

Walk(t.Right, ch)

}

}

// Same determines whether the trees

// t1 and t2 contain the same values.

func Same(t1, t2 *tree.Tree) bool {

ch1 := make(chan int)

ch2 := make(chan int)

go Walk(t1, ch1)

go Walk(t2, ch2)

// It assumes that trees node count

// is always 10

for range 10 {

curT1 := <-ch1

curT2 := <-ch2

if curT1 != curT2 {

return false

}

}

return true

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(Same(tree.New(1), tree.New(1))) // true

fmt.Println(Same(tree.New(2), tree.New(1))) // false

fmt.Println(Same(tree.New(2), tree.New(2))) // true

}With this concurrent approach, we potentially save time by pruning the comparison. We can compare values from each tree before completely traversing them.

The solution can be improved, for example, we can use channel close() at the end of traversal to check trees with different node counts. You can try to find it by yourself, or if you are interested, there are discussions of it online.

Wrap up

If you have any questions or suggestions, let’s have a chat via my LinkedIn platform. Follow Money Forward LinkedIn page for our company and blog updates.