Imagine this: What happens if our login flow fails right after the user enters their credentials?

Click “Login.” Enter credentials. Error. Click “Retry.” “Please start over.”

The user did nothing wrong, yet they have to start over because of a system hiccup.

This frustrating flow happens more often than we’d like to admit. The standard advice? “That’s just how OAuth2 works—security requires it.” We found a way to let users retry seamlessly while respecting OAuth2’s security requirements. We’re sharing what we learned in case it’s helpful.

A Bit About Me

I’m Takudai Kawasaki, a backend engineer with about 2.5 years of experience working in the Account Aggregation Division at Money Forward, using Kotlin, Java, and Golang. You can reach me via LinkedIn or X.

This project was my first time ever working on a Kotlin backend that directly serves a frontend, building for real end-users, and designing auth session management from scratch. When I say “we learned” in this post, I really mean “I learned, often the hard way.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks to FoVNull for collaborating on this design.

A Quick OAuth2 Refresher

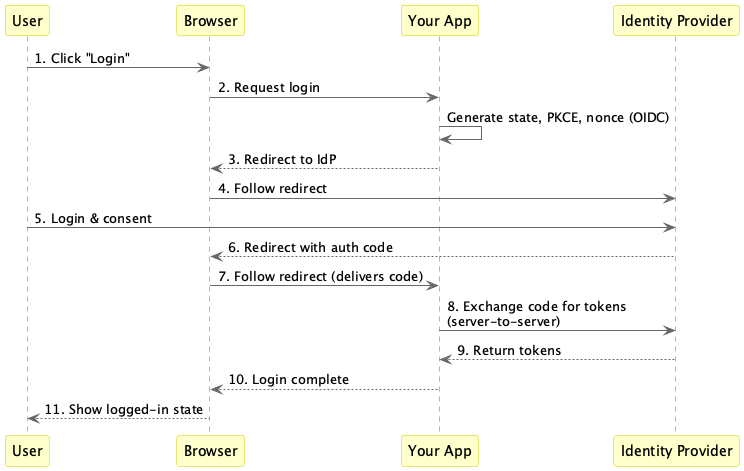

Before diving in, let’s quickly review what OAuth2 Authorization Code flow looks like.

An Identity Provider (IdP) is a trusted service that authenticates users and issues tokens—think Google, Okta, or enterprise SSO.

Key security components:

- State parameter: A random value that prevents CSRF attacks by ensuring the callback came from the same browser session

- PKCE (Proof Key for Code Exchange): Prevents authorization code interception attacks by requiring a secret

code_verifierto exchange the authorization code for tokens - Nonce: Binds the ID token to the specific authentication request

While not all are strictly required by the specifications, these are widely considered security best practices: state is RECOMMENDED in RFC 6749 for CSRF protection, PKCE is defined in RFC 7636, and nonce is specified in OpenID Connect Core.

The Problem

When a user logs in via our identity provider (Money Forward ID, Hereinafter referred to as “MFID”), and the token exchange fails due to a temporary 503 error, the standard behavior is a hard failure. The user clicks “retry” and… nothing works. Session gone. Start all over again.

(To be clear: MFID is rock-solid in production. We prepared our app to handle these 503s just in case of network blips during development and testing.)

We wanted users to retry immediately without pause. However, OAuth2 security best practices generally recommend:

- State parameters should be single-use (deleted immediately after validation)

- PKCE code verifiers should be consumed atomically

- Authorization codes should not be reused

These recommendations come from RFC 6749 (state, authorization codes) and RFC 7636 (PKCE).

Why Single-Use? The Attack It Prevents

If the state isn’t deleted immediately, here’s what can happen:

- Attacker intercepts the callback URL (via network sniffing, browser history, or logs)

- Attacker replays the same

?code=xxx&state=yyyto the callback endpoint - If a state still exists, the server accepts it as valid

- Attacker hijacks the user’s session

This is a CSRF replay attack. The state parameter exists specifically to prove that the callback came from the same browser session that initiated the request. Once validated, it must be destroyed—otherwise an attacker who obtains the URL can “replay” it.

The question: How do we preserve the user’s context while destroying the security session as required?

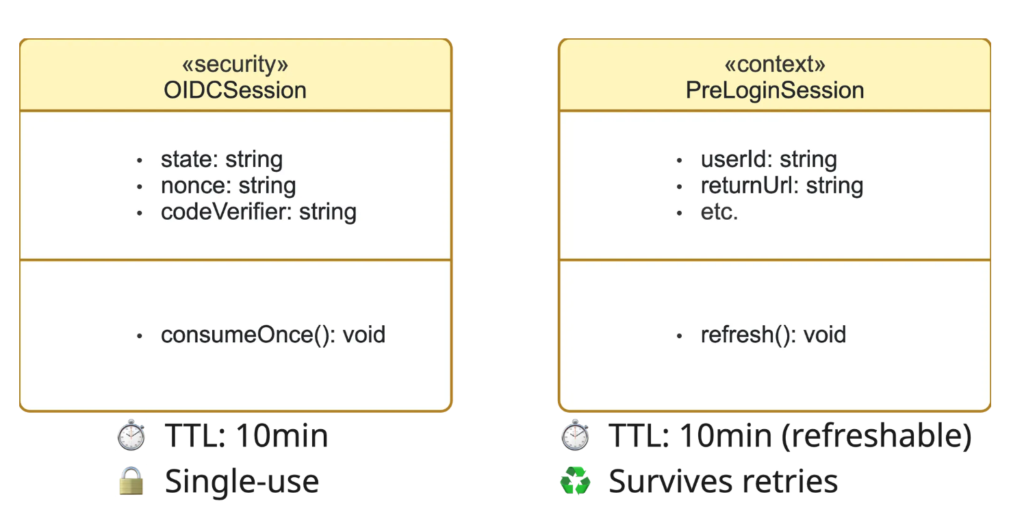

Our Approach: The Split Session Pattern

In our case, we noticed we were treating two different types of data as one. The approach we tried was to split them into two independent sessions. This isn’t necessarily the only—or even the best—solution, but it worked well for our specific situation:

| Type | Contains | Lifecycle |

|---|---|---|

| Security Session | state, nonce, code_verifier | Single-use, deleted on callback |

| Context Session | userId, returnUrl | Can persist, can be refreshed |

By separating them, we aimed to maintain security while improving user experience. This worked well for our use case.

Security Session (OIDC)

├── state → CSRF protection (single-use)

├── nonce → ID token binding

└── code_verifier → PKCE proof- TTL: 10 minutes

- Deleted: Immediately on callback via atomic GETDEL

- Never extended

Context Session (Pre-Login)

├── userId → Who the user is

├── returnUrl → Where to go after login

└── etc.- TTL: 10 minutes (but refreshable)

- Survives the security session cleanup

- Deleted: Only on successful authentication

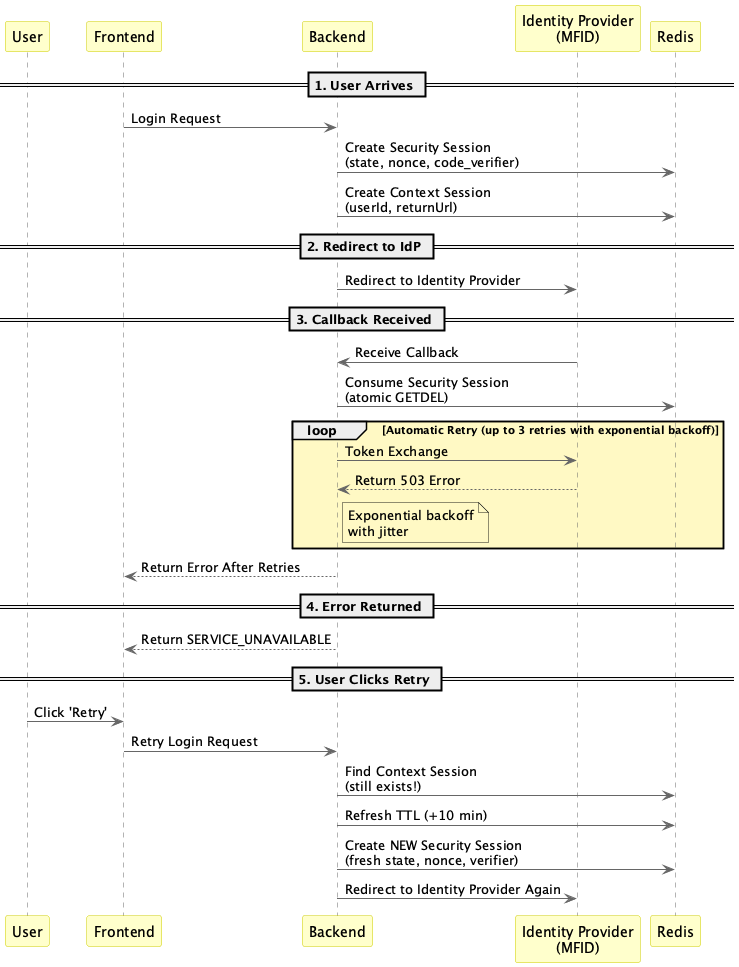

How It Works

To the user: Mostly invisible. Transient errors are retried automatically. Only persistent failures show the retry button.

To the backend: Two layers of resilience—automatic exponential backoff for transient errors, plus the Split Session Pattern for persistent failures requiring user action.

Key Implementation Details

Atomic Consumption

The security session uses Redis GETDEL read and delete in one atomic operation. No race condition where two requests could both read the same state.

Why atomic matters: Without atomicity, a race condition exists where two parallel requests could both validate the same state before either deletes it.

Concurrent retries: Atomic GETDEL handles this naturally—only the first request consumes the session; others fail gracefully.

Security Session Lifecycle on Failure

A common question: what happens to the Security Session when a token exchange fails?

The key insight is that the Security Session is consumed before the token exchange even begins. The flow works like this:

- Callback arrives with

?code=xxx&state=yyy GETDELatomically retrieves and deletes the Security Session (state validated, session gone)- Token exchange is attempted using the retrieved

code_verifier - If the token exchange fails → the user sees the “Retry” button

- Retry creates an entirely new Security Session (fresh

state,nonce,code_verifier) - User is redirected to IdP with

prompt=login - Fresh authorization flow begins

What about the old session?: It’s already gone—consumed by GETDEL in step 2. There’s no “old session” lingering. If the user abandons the flow without clicking retry, the Context Session simply expires via its TTL.

Why not preserve the Security Session on failure?: This would violate the single-use principle. Once state is validated, it must be destroyed—even if subsequent steps fail. Keeping it around would open the door to replay attacks.

Automatic Retry with Exponential Backoff

Before returning an error to the user, the token exchange automatically retries transient failures:

- 4 attempts total (initial + 3 retries)

- Exponential delays: ~1s → ~2s → ~4s

- Jitter: Random 50-100% multiplier prevents thundering herd when the IdP recovers

Retryable conditions:

- HTTP 5xx server errors (503 Service Unavailable, 500 Internal Server Error)

- OAuth2 error codes:

temporarily_unavailable,service_unavailable - Network timeouts and connection errors

This means users only see the “Retry” button for truly persistent failures—single transient 503s are handled transparently in the background.

Independent TTLs

The context session has its own 10-minute TTL that starts when the user first arrives. It can outlive multiple OAuth attempts. Each retry refreshes it by +10 minutes.

Safety limits: To prevent indefinite extension, we enforce a maximum absolute lifetime of 1 hour and cap retries at 3 attempts. After either limit is reached, the user must start a fresh login flow.

Session Independence

The two sessions use independent keys: the security session gets a fresh random state on each attempt, while the context session is identified by a separate cookie. This ensures cryptographically fresh security parameters while user context persists separately.

Forced Re-authentication

On retry, we pass prompt=login to the identity provider, forcing a fresh login screen instead of using any cached session. This ensures the user actively re-authenticates rather than silently reusing a potentially stale IdP session.

Multi-Tab Behavior

What happens when a user opens multiple tabs and starts the login flow in each?

- Each tab gets its own Security Session with independent

state,nonce, andcode_verifiervalues - Context Session is shared across tabs via a browser cookie (same browser = same cookie)

- First tab to complete wins – its callback consumes both its Security Session and the shared Context Session, completing authentication

- Other tabs will fail when their callbacks arrive – not because their Security Sessions are invalid (each tab’s Security Session is independent and can be consumed), but because the shared Context Session was already deleted by the first successful tab

This is expected and safe behavior. The callback handler requires the Context Session to validate user correlation, and that session only exists once. The user only needs one successful login. Failed tabs can simply be closed, or the user can click “Retry” which starts a fresh flow.

Edge case: If the Context Session’s userId differs between what was stored and what the IdP returns (e.g., user logged into a different account), authentication should fail with a clear error. This prevents session confusion attacks. See Security Prerequisites for more details.

Security Prerequisites

Before implementing this pattern, ensure the environment meets these requirements. Each prerequisite addresses a specific attack vector:

| Prerequisite | Spec Reference | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

IdP respects prompt=login | OIDC Core §3.1.2.1 (OPTIONAL) | Must force re-authentication, ignoring cached IdP sessions. If the IdP ignores this parameter and silently reuses a cached session, the user might authenticate as a different account than intended. |

| Short Authorization Code TTL | RFC 6749 §4.1.2 (RECOMMENDED ≤10min) | Authorization codes should expire quickly. MFID uses the RFC’s recommended maximum of 10 minutes, which means a longer window where multiple valid codes could exist—making atomic consumption of security sessions particularly important. |

| Atomic Read-Delete guarantee | Implementation-specific | The session store must support atomic read-and-delete (like Redis GETDEL). For Redis clusters, ensure consistent slot routing so the operation isn’t split across nodes. Without atomicity, race conditions could allow the same state to be validated twice. |

| UserId binding verification | Implementation-specific | The userId in the Context Session must be verified against the authenticated identity from the IdP. This prevents an attacker from starting a flow, obtaining a Context Session, then completing authentication with a different account. |

| Secure cookie attributes | RFC 6265bis (general web security) | Session cookies must use HttpOnly (prevents XSS access), Secure (HTTPS only), and SameSite=Lax or Strict (prevents CSRF). Without these, attackers could steal or forge session cookies. |

Note: OAuth/OIDC specs use “SHOULD” and “RECOMMENDED” (not “MUST”), meaning IdP compliance varies. Always verify the IdP’s behavior for spec-defined parameters like

prompt=loginand authorization code TTL.

What If a Prerequisite Isn’t Met?

- IdP ignores

prompt=login: Users might silently authenticate as the wrong account on retry. Consider usingmax_age=0as an alternative (per OIDC spec, “max_age=0 is equivalent to prompt=login”). - Long Authorization Code TTL: Increases the window for code interception and replay. Work with the IdP to reduce this or implement additional code binding checks.

- Non-atomic session operations: Race conditions become possible. Consider using database transactions or choosing a different session store.

- Missing UserId verification: Session hijacking becomes possible where an attacker’s authentication completes with a victim’s Context Session.

- Insecure cookies: Session tokens can be stolen via XSS or network interception, or forged via CSRF.

When This Pattern May Be Useful

Based on our experience, this approach may be worth considering when:

- The IdP has occasional availability issues — 503s, timeouts, network blips happen

- Retry UX matters without compromising security — users shouldn’t start over for transient errors

- The system uses OAuth2/OIDC with PKCE — where state, nonce, and code_verifier must be single-use

- The flow involves pre-authentication context — user ID from upstream, return URLs, app context

It’s probably overkill if the IdP is extremely reliable or if users can easily restart the flow (e.g., just clicking “Login” again from a homepage).

The Outcome

Users can now retry failed logins without starting over. We believe security is maintained—state is still single-use, PKCE is still enforced, authorization codes are still consumed atomically.

Key Takeaway

When balancing security constraints with user experience feels difficult, it might be worth asking: Are two different concerns being treated as one session?

The Split Session Pattern – separating ephemeral security state from persistent user context – was our answer to this question in our specific context.

For our use case, separating concerns helped us improve the user experience without compromising security.

Further Reading

- RFC 6749: OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework — The foundational OAuth2 specification

- OpenID Connect Core 1.0 — The OIDC specification defining

prompt,nonce, and authentication request parameters - RFC 7636: PKCE Extension — Proof Key for Code Exchange specification

- Auth0: State Parameters — Practical guide to state parameter usage

- OWASP OAuth Cheat Sheet — Security best practices for OAuth implementations