Hi, I’m Alex Wilson and I’m a Staff Engineer in the Business Platform Development Division of Money Forward. Welcome to day 5 of our 2025 advent calendar.

In 2025, we overhauled one of our customer-facing products to make it faster, more secure and more reliable.

We achieved this by consolidating business logic to run on the server, server-rendering with React Server Components, and unlocking both of these things by migrating to the Next.js App Router.

In this post I want to talk about how we did this, and about the challenges we faced along the way.

Chapter 1. The Challenge

We build many web applications with Next.js, which is a framework for building full-stack React applications.

Next.js and its routers

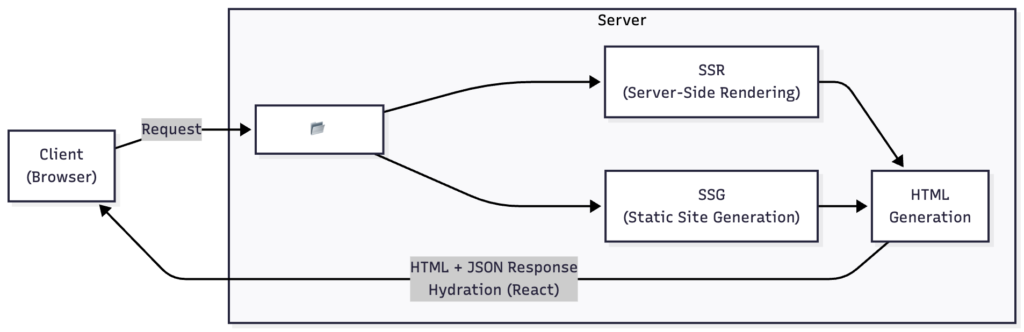

Before Next.js version 13, its primary architecture was called the Pages Router, which would detect React Components in a src/pages directory, allow them to do some data-fetching and then compile these into the actual pages/views shown to users. For most applications, this means that the work to show UI happens both on the server and then again in the browser.

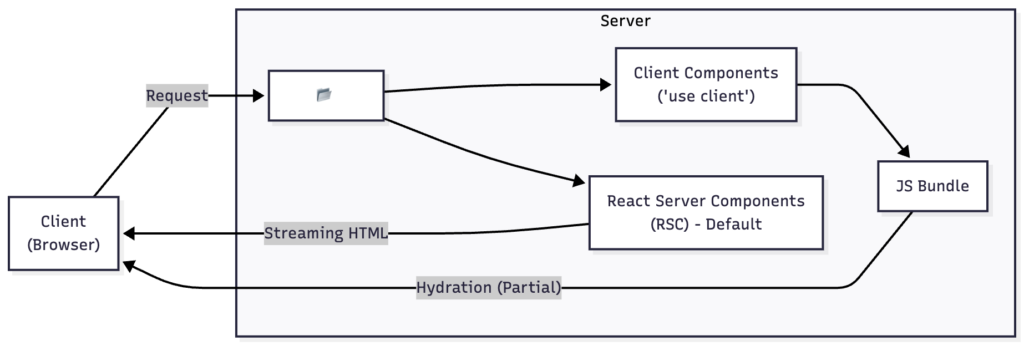

With version 13, in partnership with the React team, Next.js introduced a new architecture called the App Router, which changed many things but enabled two new major features in React: React Server Components and React Server Actions. React Server Components are React components which only execute on the server. Optionally, in this architecture, existing React components can now request to only be rendered on the client.

At time of writing, Next.js have not announced an official schedule for the Pages Router to be deprecated, but many new features introduced since 2023 only target/support the App Router.

Why migrate?

Aside from wanting to align with the long-term technical directions of both React and Next.js, we anticipated these benefits:

- Improved user experience: Moving work such as data-fetching and complex validation server-side means that users encounter fewer unhandled error scenarios. React also includes features like Suspense which give us the opportunity to add animations and transitions.

- Improved code quality: A clearer separation between data-fetching/validation and UI code means that we can re-use more of it, and test it much more thoroughly.

- Faster page-loads: The changes result in smaller, faster and snappier web-pages and web-apps leading to increased engagement, retention and conversion which are always welcome.

OK, but why did you migrate now?

OK, so the benefits sound good, but if there’s no deadline, why migrate at all?

In short: It wasn’t just about the App Router, so if you’re here only for that, you can skip ahead to Chapter 2.

On top of the benefits above, we thought that migrating to the App Router was a golden opportunity to revisit our frontend architecture. We would also learn what a migration to the App Router actually involves for our other products when a Pages Router deprecation is scheduled.

Our starting position

Many of our smaller applications are built using the Pages Router, and are thin UI layers on top of robust backend APIs. This approach has allowed originally more backend-heavy teams to quickly build out rich products, however has drawbacks:

- Maintenance costs compound: These backend APIs are tightly coupled to frontends, and as product functionality expands so too does the time required to launch & support features.

- User experience options are limited: This approach means that logic usually runs client-side, but that it’s sometimes optimistically run server-side, and this inconsistency translates directly to the user experience.

And so, anticipating more UI-heavy feature development in one of our products, we thought that this was the right time to migrate it and overhaul it in the process.

Chapter 2: The Plan

Before anything else, we followed the official migration guide to do a (very) basic proof-of-concept to see where the edges would be.

Proving the concept

In a temporary branch, we deleted all but one of our pages, and renamed the src/pages directory to src/app (step 1), copied in a blank layout (step 2) and extracted our client-only state-management (Providers). From here we removed functionality and customizations one-by-one until we were able to compile, which gave us which areas we needed to focus on:

Problem 1: There was a problem with our configuration

Our code-base collocated pages, components and tests by leveraging the custom file-extensions parameter. We removed our tests and separated its components which let our application compile!

Problem 2: None of our error handling worked

In the App Router, error handling changed significantly, with “Not Found” being executed as a catch-all route server-side, and all other errors moving to an Error Boundary which is caught client-side.

Our error-handling code had been built to execute on both server-and-client, so we temporarily removed all of the server-side error handling.

Problem 3: Some of our UI dependencies wouldn’t server-render

Some third-party dependencies made use of features that only worked on the client but didn’t specifically opt-out of server-rendering. To solve this, we followed the same pattern we’d used for client-only state management: Split some of our React components into server-only components to act as a “shell”, and inner client-only components.

import LikeButton from "./LikeButton";

export default function Page() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Post title</h1>

<LikeButton />

</div>

);

}

"use client";

import { useState } from "react";

export default function LikeButton() {

const [liked, set] = useState(false);

return (

<button onClick={() => set(!liked)}>

{liked ? "❤️" : "♡"}

</button>

);

}

By making these changes, we were able to compile, log-in and perform some basic operations! Great, so all we need to do is solve these things, and it’ll all be fine! Famous last words.

All that was missing from our plan was a release strategy. From the pilot, it was clear that the migration would take some time. To minimize risk and disruption to users, we couldn’t do this as a big-bang release, and we also couldn’t suspend routine feature development & bug fixing. This meant that a period of dual-running was unavoidable.

And so we formed a four-step plan:

- Enable the App-Router: Let it take over all error-handling, but without it handling any other user-facing functionality.

- Release one page: Find a candidate new feature, build it in the App Router and release it as normal.

- Progressively migrate other pages: Integrate feature-flagging, duplicate pages and port them and their shared dependencies and release them one-by-one behind a feature-flag.

- Remove the Pages Router completely: Remove remnants of the Pages Router, and revert all changes we make to enable dual-running.

Great. Let’s go!

Chapter 3: Switching on the App-Router

Ultimately this proved to be the most time-consuming step, because all we did in the proof-of-concept step was avoid solving these first two problems.

Changing our Page Extensions

Problem 1 was that our existing folder structure wouldn’t reliably compile, and when it did compile, all pages would throw an error.

To explain this, we need to look at what a stock-configuration Pages Router page looks like:

src/pages/[test].tsx

src/test/pages/[test].test.ts

src/components/[test]/test-component.tsx

src/test/components/[test]/test-component.test.tsHere, [test] is the actual path used for the page, and this pattern is baked into the filename of the page

This is OK at first, but as the number of pages, components and their test cases grow, it can become quite difficult to keep track of everything, and so many people collocate components together.

In the Pages Router, you can use the pageExtensions configuration parameter to enable this:

// next.config.js

module.exports = {

pageExtensions: ['page.tsx', 'page.ts', 'api.ts']

}And then our folder structure looks more like this, where .page.tsx is what NextJS is looking for, and the route is still /[test]:

src/pages/[test].page.tsx

src/pages/[test].test.ts

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.tsx

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.test.ts

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.stories.ts

Luckily, collocation has become the norm, and the equivalent in the App Router looks like this:

src/pages/[test]/page.tsx

src/pages/[test]/page.test.ts

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.tsx

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.test.ts

src/pages/[test]/components/test-component.stories.tsIt should be as simple as keeping the .page.tsx extension, right? Unfortunately, no. At time of writing, the pageExtensions parameter is effectively unsupported in the App Router (Next.js #23959, #65447).

Aside from a few of the solutions in related GitHub issues, here’s what we tried:

- ❌ Using

.page.tsxfor both – App Router build fails - ❌ Using

.tsxfor both – Page Router picks up test/story files as routes - ❌ Separating all collocated files – Massive refactor that would be too disruptive for ongoing work for our period of dual-running

Why not both?

A throwaway comment of, “Why not try everything at the same time?” went a bit too far, and we realized that we could:

- Bulk rename

src/pagesto something likesrc/pagerouter_pages, which is one change in Git and won’t break anyone’s workflows. - Create proxies for all of the pages in the

src/pagerouter_pagesdirectory, in a newsrc/pagesdirectory. And by automating this, we could hook it into our existing NPM workflow. - Remove the custom

pageExtensionsconfiguration completely, allowing the App Router to compile, and for the application to load.

And so that’s what we did. We wrote a script which automatically generated proxy classes which re-exported all .page.tsx exports from the freshly renamed pagerouter_pages directory.

The source-code for this script is available here:

alexwilson/b1e4fa1eb0017c67132c25eb1c134e5e

But hopefully this will be fixed soon.

Rebuilding Error-Handling

Problem 2 was that our existing error-handling did not work.

We started with a typical JavaScript-style error handling: Try/Catch blocks on individual operations, and a top-level catch which would attempt to recover uncaught errors, show a toast to users and then finally log them.

What we needed (at minimum) was: A global Error Boundary and a “Not Found” page. Creating these was quite easy, we repeated what we’d done in the proof-of-concept.

But we still needed server-side error handling.

Luckily all our existing API calls were made using the Axios library, which supports the concept of Interceptors.

Interceptors allow us to catch errors returned by API calls, and so we started by mirroring our previous top-level server-side error handling.

For local and more specific error-handling scenarios, we chose to handle them whilst migrating related functionality.

Run-Time Configuration

Something we missed in the proof-of-concept is that while Next.js’s Pages Router supports setting/changing application configuration at run-time, the App Router does not.

This makes perfect sense: If you’re statically compiling JavaScript for the browser in a CI environment, it will only have access to the variables available in that environment, even if we are using different information in production.

We used this Pages Router pattern a lot:

import getConfig from 'next/config';

export function Component() {

const { publicRuntimeConfig } = getConfig();

return (

<header>

<a href={publicRuntimeConfig.baseUrl}>Some Link</a>

</header>

);

}

We build & artefact all of our systems in a CI environment before deploying them to a cluster where we set run-time variables all the time, and so not being able to do this was a deal-breaker.

We needed a solution that would work for both Page and App Router. Theoretically all it needed to do was conditionally read some runtime state from the server when in the App Router context, and for Page Router pages fall-back to the Pages Router the existing publicRuntimeConfig API.

We found a nice package called next-runtime-env which met our security standards and which would handle transmitting the state in App Router.

NOTE: At time of writing, this package doesn’t support all versions of Next.js 15, or Next.js 16.

With the help of this package, we wrote a small internal abstraction layer which surfaced an almost identical API to publicRuntimeConfig which made rolling it out quite easy:

import { env as appRouterEnv } from 'next-runtime-env';

// Map of config property name to environment variable name

export const PUBLIC_RUNTIME_CONFIG_MAP: Record<string, string> = {

baseUrl: 'NEXT_PUBLIC_SOME_URL',

};

export function getPublicRuntimeConfig() {

const config: Record<string, string | undefined> = {};

// Populate object matching original publicRuntimeConfig

for (const [key, envVar] of Object.entries(PUBLIC_RUNTIME_CONFIG_MAP)) {

config[key] = appRouterEnv(envVar) || undefined;

}

return config;

}

Usage looks something like this:

import { getPublicRuntimeConfig } from '@lib/publicRuntimeConfig';

export function Component() {

const publicRuntimeConfig = getPublicRuntimeConfig();

return (

<header>

<a href={publicRuntimeConfig.baseUrl}>Some Link</a>

</header>

);

}Switching it on

Phew. That was a lot. But it seems to be working fine now!

However, since we’ve now touched a lot of functionality (including all error handling), our next step was to check for any new bugs and errors by running a Bug Bash. No major issues.

And, after all that, finally, we switched the App Router on.

Chapter 4: Migrating our first page

Now that the App Router is running, we can begin the “migration” part of the migration. Here we’re taking an in-development feature adding a new page, and working with the responsible team to build it directly into the App Router.

This should be a win for everybody, because App Router pages require far less boilerplate than their Pages Router counterparts. But what’s missing?

Supporting shared components in both routers

This proved to be relatively straightforward?

Originally we saw an issue with our dependencies where they would attempt to use client-only features on the server, but during the real thing we narrowed this down to only one package.

We mitigated this issue almost completely by finding references to this dependency and forming new boundaries between server & client components around it.

We did this almost identically to during our pilot, by adding splitting components and adding "use client"; directives to the ones directly including this dependency.

Authentication & Middleware

The next issue was auth.

A common pattern in single-page applications is to assume users are signed in and have access to stuff, and to then catch 400/403 errors in API calls and modify the UI based on this. This is a gross simplification, of course, but initially, we did something like this by catching errors thrown on per-API-call level.

However now that we’re handling errors differently, this approach doesn’t work (and has become inexplicably much slower?)

Here, Next.js’s recommendation is to use middleware. All of our products already use some form of session, so we can implement this in a stateless way.

However, Next.js 12 deprecated structured/staggered Middleware, and has instead moved Middleware to a single file. We were looking to structure our middleware to separate concerns like auth. This is where Next.js Easy Middleware (NEMO) came in.

We built a small auth middleware that attempted to validate a session, and if it was invalid, would send users to their login page.

Metadata API

The Metadata API replaces previous usage of the next/head component, and honestly this was very simple to adopt. It’s fewer lines of code and far more predictable.

Our first App Router page

A feature-team was building new functionality which added a new page (instead of modifying any existing ones), and so we partnered to build it as an App Router page. This meant less boilerplate. It went through testing as normal, found no issues, and released without issue.

Great, now we have an App Router page in production!

Chapter 5: Migrating everything else

Now for the real challenge: Migrating everything else.

At this point, both the App Router and Pages Router are serving traffic, with the App Router handling global error handling, and auth logic happening in middleware.

Feature Flagging

We had already integrated a feature-flagging library called Flipt which would segment users based on their session.

To port pages to the App Router, we copied them and ported their boilerplate to the App Router layout, and put them under a new prefix.

However, how do we actually send users to this new page? We built a new middleware, chained to execute after auth, which would evaluate the feature-flag and perform an internal rewrite, and it looked like this:

// src/middleware/page-to-app-migration.ts

const ROUTER_MAPPING = new Map<string, string>([

['/page', '/..app-router/page'],

// ... more mappings

]);

export const middleware = async (request: NextRequest) => {

const url = new URL(request.url);

// Check if this path has an App Router version

if (ROUTER_MAPPING.has(url.pathname)) {

const flag = await getFeatureFlag('pageToAppMigration');

if (flag.enabled) {

url.pathname = ROUTER_MAPPING.get(url.pathname);

return NextResponse.rewrite(url);

}

}

// Otherwise, continue to Page Router

return NextResponse.next();

};next/router/compat

How do components (for example, pagination?) push navigation changes?

One crucial change between Pages Router and App Router is a move from the next/router hook in the Pages Router to next/navigation hook in the App Router. They offer similar functionality, but since they are dependent on the router, they are incompatible with one another and importing the wrong one throws an irrecoverable error.

Next provides a next/router/compat module which can be imported into App Router pages, however, when used in the App Router it doesn’t do anything: All compat does here is return null.

Similarly, the next/router supported “shallow” pushes which is when the client adjusts the URL without performing a full server-driven re-render. We use this pattern a lot in areas like search when the user changes something but we don’t need to perform a full re-render.

So to make components compatible with both routers, and to keep shallow pushes, we wrote a new hook which uses both routers:

// hooks/useRouterPush.ts

import { useRouter as useNextRouter } from 'next/compat/router';

import QueryString from 'qs';

export const useRouterPush = <T extends Record<string, unknown>>() => {

const pageRouter = useNextRouter();

const push = (params: Partial<T>, options?: { shallow?: boolean; href?: string }) => {

const query = QueryString.stringify(params, { arrayFormat: 'brackets' });

// Try Page Router first

if (pageRouter?.push) {

pageRouter.push(

{ pathname: options?.href || pageRouter.pathname, query },

undefined,

{ shallow: Boolean(options?.shallow) }

);

}

// Fall back to Web History API for App Router

else {

const url = options?.href || window.location.pathname;

window.history.pushState({}, '', `${url}${query ? `?${query}` : ''}`);

}

};

return { push };

};From Client Components to Server Actions

Some functionality which had been client-based saw a major slowdown when we moved to the App Router, even when we attempted to opt-out of Server Components by using the ”use client”; directive.

We weren’t able to fully explain this slowdown, but we believed it was related to preloading. So to address this, we ported their functionality to Server Actions.

This resulted in the double-whammy of a reduction in boilerplate (and easier testing), as well as even faster performance than pre-migration:

1. Form-based mutations with Server Actions

<form action={serverAction}>2. Server-side redirects after mutations

'use server';

export async function doSomething(id: string) {

await api.something(`/${id}`);

redirect('/');

}Another nice benefit is that these are progressively enhanced by default meaning that if client-side JavaScript fails for some reason this functionality will now continue to work!

Release train

From this point, we followed the above steps to fully migrate all remaining components and pages, to test them, and then launch them one-by-one.

This would not have been possible without feature-flagging, which allowed us to switch on & off the new App Router pages. We began by targeting them at our internal tenant first, and then rolling out to users sequentially.

After App Router pages seemed stable, we began graduating them by removing them from the mapping table in our middleware, and deleting their Page Router equivalents.

Chapter 6: We’re on the App Router

OK! Now we have all of our pages running in the App Router, and we’ve deleted all of our Pages Router pages.

We now have:

- A routing compat hook

- Feature-flagging middleware

- The original Pages Router layout

- A workflow which attempts to proxy Page Router pages

Taking advantage of the App Router

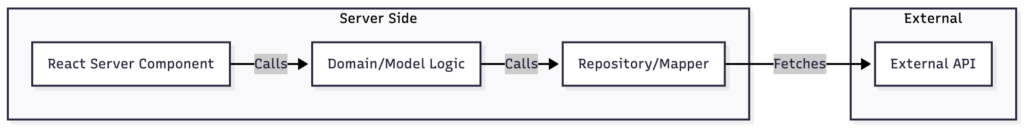

One of the major benefits of the App Router was letting us revisit our business logic, and so we took full advantage of this for both server & client rendering.

We introduced a “domain layer” which sits between Pages and our backend APIs, allowing us to separate our views and our data with versions of Model-View-ViewModel & Repository patterns.

Meaning that our business logic now looks like this:

- View (React Components)

- Model & View Model (Business logic in entities/*/index.ts)

- Repository (Mappers in entities/*/mapper.ts)

- Data sources (API clients)

Caching

This application is fully user-dynamic, so we did not change or modify the caching strategy during the migration. This is an area for future improvement.

Deleting all of the things

We chose to keep our routing hook, because it was a useful abstraction in general. So we added more testing around it and have kept it. It would be useful to see shallow-routing functionality in future.

But other than this, we no longer need any of the features/changes we made to support dual-running the App Router and Pages Router. This made for a very satisfying series of commits which were (mostly) deleting code.

Chapter 7: Conclusion

What did we get?

- We’re now on the App Router, and we were able to do it in our own time.

- Our client-bundles are smaller, and some core journeys (esp. sign-in) are significantly faster.

- Moving more logic to Middleware has allowed us to centralize core functionality and reduce boilerplate across the board.

- Server Actions have let us separate concerns between view logic and business logic, and to introduce an abstraction that makes it easier to develop frontend & backend independently.

- Better automated testing.

What went well?

- Feature-flagging helped us reduce risk as we migrated from one router to the other.

- TypeScript came in clutch constantly during this project. All of the subtle deprecations and changes were flagged immediately, which combined with enforcing strict typing (including now banning use of the

anykeyword!) let us completely avoid (probably) thousands of bugs. - Dual-running went well, and since we were able to avoid any major workflow changes we didn’t suffer any major slowdown of feature-development.

What didn’t go so well?

- It took ages: If we had done a “big-bang” migration, it would have been much faster: Dual-running and avoiding disrupting ongoing development added a lot of complexity to the actual migration which already had its own challenges.

- Migration documentation is lacking: Behavioral changes like pageExtensions, error-handling and

next/navigationnot fully supporting allnext/routerfeatures are things we discovered during development but would have liked to know up-front. - Automated testing: Our unit-level tests weren’t very useful as we moved logic between architectures which required rewriting big blocks of code, and our end-to-end test coverage wasn’t enough on its own, so a lot of manual testing was required. We’re left with better tests and coverage across the board now.

What would we change for future migrations?

- Establish solid end-to-end testing first: We could test our most critical journeys, but there were more complex scenarios which weren’t automated at the time.

- Build more abstractions: When we abstracted framework features like runtime configuration, navigation/routing, etc. it became simple to make them support Pages Router, App Router and both, and we chose to keep some of these abstractions in the long-term.

- Freeze other development: Dual-running posed interesting challenges, but especially now we know where the workflow changes will be, it’s simpler not to dual-run and to freeze development for a short while.

Was it worth it?

Overall yes. Between our rationalization work and the new architecture of React & Next.js’s App Router, this product now has a solid foundation for the next few years of feature development. And we now know where the rough-edges of a migration are for future App Router migrations!

Closing thoughts

There are many people to thank, but in particular I want to thank my colleagues Emanuele Vella, Quan Le & Tomoaki Yoshioka for all their work during this major re-architecture and improvement project. None of it would have been possible without them!

We learned a lot: And I hope that our lessons learned can both convince you to move to the App Router and re-embrace the server, as well as to save you some time along the way.